The Rooster In Flight - A Substack Article

Let’s talk about this t-shirt

What I Learned from a Stranger in a Bold Slogan T-Shirt in LAX

By: Wynand Johannes de Kock

May 19, 2025

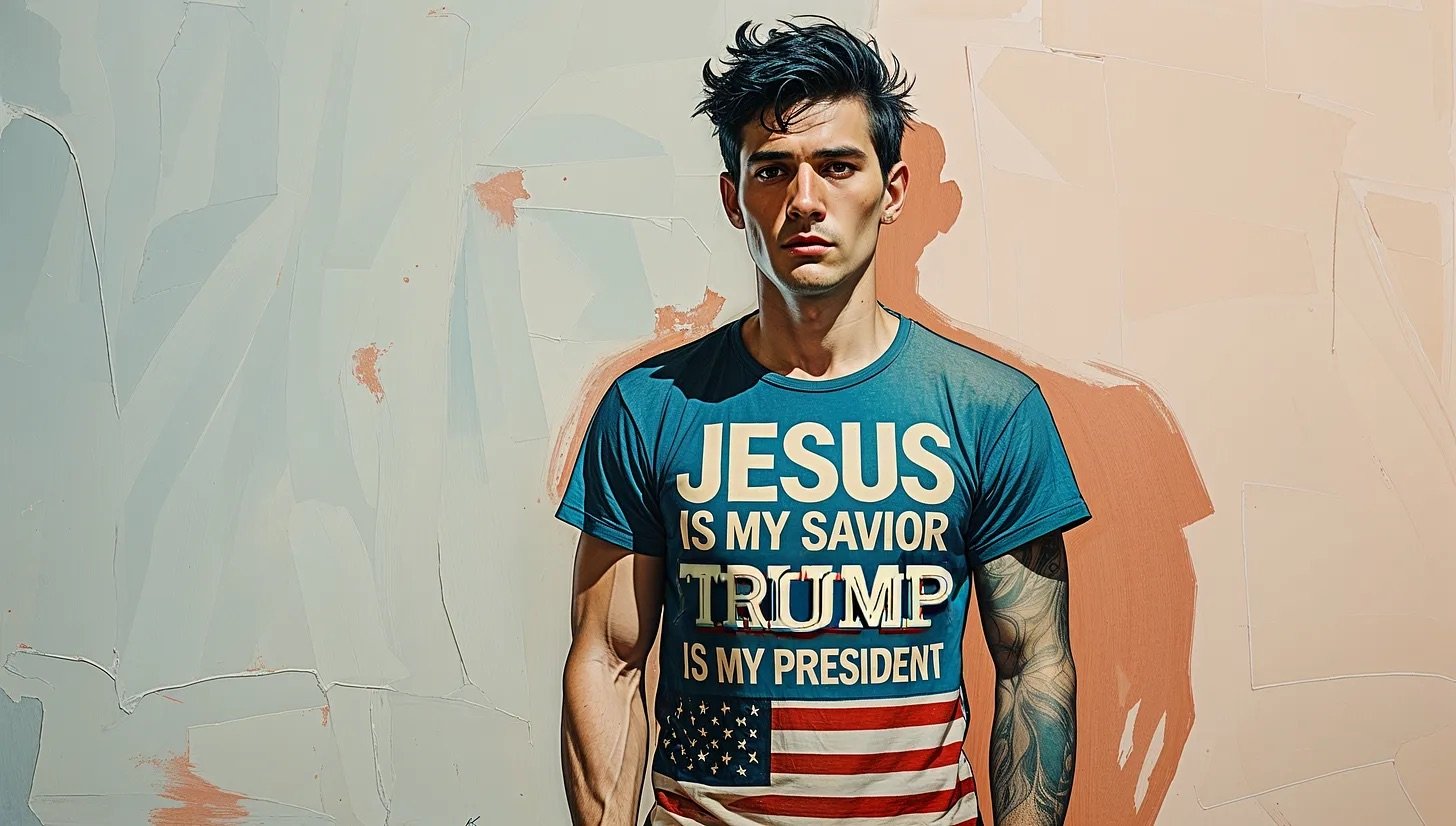

Dear Brother in the “Trump is my President, Jesus is my Savior” T-shirt

Remember me? We shared that liminal space of terminal purgatory at LAX—you with your Driscoll book splayed open like scripture, me with my book, "On Being in The Middle: Doing Theology in the Face of Uncertainty" on my lap You leaned over and said, "The title seems soft." And all of a sudden, you became this introvert's worst nightmare. Our delayed flight stretched between us like the Jordan River: you on one bank, "Trump is my President, Jesus is my Savior" stretched boldly across your chest, Driscoll's "Real Marriage" splayed open on your lap, me on the other, both claiming the same Christ but seeing different kingdoms.

I've been thinking about your T-shirt.

Not just the cotton blend or the bold typography, but the theology it performs-the way it binds together two names, two authorities, two kingdoms in a marriage no prophet would bless. Trump and Jesus, paired like wine and wafer on your chest, a communion of power that makes me wonder which one truly transubstantiates into the other.

Let me tell you about my South Africa.

Before democracy bloomed in 1994, our pulpits thundered with certainties. White dominees (the Afrikaans title for pastors, which ironically means lord or master) proclaimed apartheid as God’s design-a ‘separate development’ blessed by scripture. They found verses to sanctify barbed wire, to baptise bulldozers flattening Black homes, to anoint the sjambok, a long, stiff whip, originally made of rhinoceros hide. They wore their theology like you wear that T-shirt: a declaration of divine right, a uniform of unquestioned authority.

Their Jesus had blue eyes, in army fatigues and carried a rifle.

When Desmond Tutu spoke of a Black Christ who suffered with township children choking on tear gas, they called him a Communist. When Beyers Naudé recognized his complicity and crossed the line to stand with the oppressed, they stripped him of his credentials. When Allan Boesak preached that God sides with the downtrodden, they dismissed him as "political," as if politics only exists when it threatens power, never when it enforces it.

I wonder if you see the parallels.

Your Driscoll preaches a God with genitalia-a divine phallus that somehow makes men more image-bearing than women. Your Trump performs a strength that never kneels, never apologises, never washes feet. Between them, they've constructed a theology of power that looks nothing like the Galilean who died naked, shamed, and abandoned on a trash heap outside Jerusalem.

What gospel is this? What good news for the poor does this muscular Christianity offer?

In the terminal, you spoke of "real men" with such certainty—as if masculinity were a doctrine to defend rather than a cultural performance that shifts like sand between our fingers. You cited chapter and verse about male headship with the confidence of someone who has never had to wonder if God's image includes his body.

But here's what haunts me: the way you spoke of Jesus.

Not as the one who touched lepers and ate with prostitutes, but as a conquering CEO with a corner office in heaven. Not as the one who said "the last shall be first," but as the one who ensures your first place stays secure. Not as the one who emptied himself of divine privilege, but as the one who guarantees yours.

Interested in completing the article? Follow Wynand on Substack